Have you ever seen an advert appear on your Facebook or Instagram feed, so specific that you can only accuse your smartphone of listening to your conversations? That there’s no way it could have been targeted at you unless the microphone has been on and listening without your consent? Well, you’re wrong.

Surprisingly this is not the case, both Facebook and Google reject the accusations that their services can use smartphones to gather information in this way, and there are data usage and developer policies in place to ensure third party app developers cannot do this either, so no, your conversations are not being secretly eavesdropped upon. But unfortunately, the truth is much more disturbing.

“If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product” is a quotation most will have heard, but few understand. In this sense, the product is your identity; who you are, where you go, your age, gender, weight, relationship status, friends, career, income, political views, religion, fears, dreams and aspirations. Just to name a few. By using products or services that are ‘free’, in return, you are agreeing for the provider to capture and store your identity.

However as this is the case, the quotation above is fundamentally self-contradicting, the product is being paid for, but with a means other than currency. This raises questions such as: If I am paying for this ‘free’ product, how much is it? Am I overpaying? Who has access to my data and how is it being used?

But most alarmingly of all, many will simply ask… who cares?

The Extent

Living in the 21st century during an era of technological revolution, every one of us should be aware that what we do online, and everything we use electronic devices for, is no longer private. To use everyone’s favourite search engine as an example, Google is very much at the forefront of today’s data harvesting controversy, and it would be naïve to think that it’s only your search history that’s being stored. As part of my research, I requested all the data that Google holds on me.

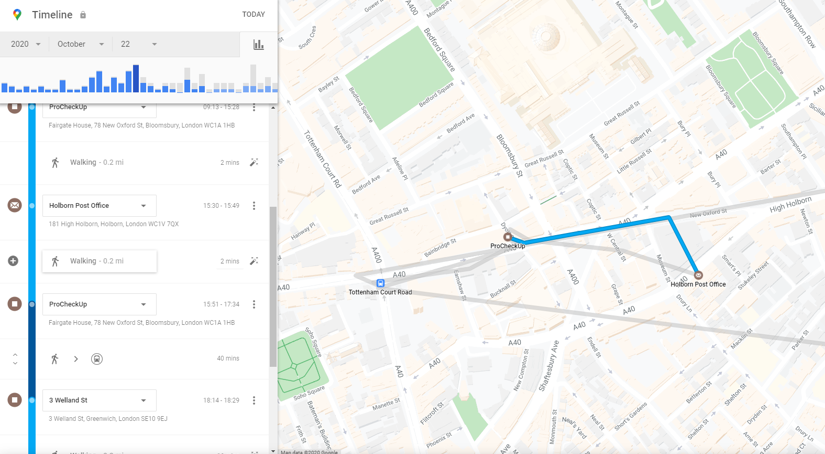

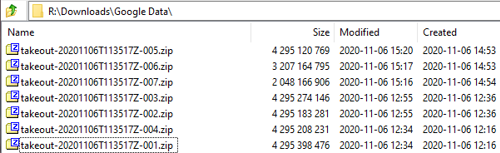

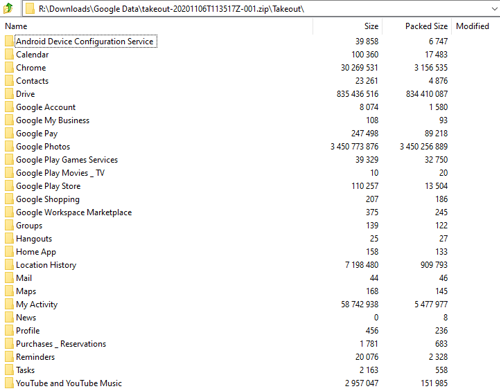

Several days later, in return I was provided with 24.9 gigabytes worth of material on myself. To put this into perspective, that’s approximately 1 million text-based word documents containing information extending far beyond just my search history. I trawled through an archive including exactly where I have been for the past two years (specific to the co-ordinate), how long I was there (specific to the millisecond), and how I got there (including likely mode of transport).

"location" : { "location" : {

"latitudeE7" : 515168610, "latitudeE7" : 515164448,

"longitudeE7" : -1280194, "longitudeE7" : -1239106,

"placeId" : "ChIJgScPezEbdkgRSobFf8Niees", "placeId" : "ChIJyxp4PLMEdkgR6Tbj7o3vyl0",

"address" : "Fairgate House\n78 New Oxford St\nBloomsbury, "address" : "181 High Holborn\nHolborn, London\nWC1V

"name" : "ProCheckUp", "name" : "Holborn Post Office",

"sourceInfo" : { "sourceInfo" : {

"deviceTag" : -948015213 "deviceTag" : -948015213

}, },

"locationConfidence" : 98.52276 "locationConfidence" : 83.78965

}, },

"duration" : { "duration" : {

"startTimestampMs" : "1603354428796", "startTimestampMs" : "1603377009631",

"endTimestampMs" : "1603376894978" "endTimestampMs" : "1603378157691"

}, },

"distance" : 163,

"activityType" : "WALKING",

"confidence" : "HIGH",

"activities" : [ {

"activityType" : "WALKING",

"probability" : 97.22506999969482

}, {

"activityType" : "CYCLING",

"probability" : 1.197645254433155

In addition to this, I was able to listen to audio recordings of anytime I’ve used Google’s voice assistant, I was able to see every app I’ve ever downloaded to my phone and the data they have collected, every website I’ve visited and how long for, every YouTube video I’ve ever watched, every email sent/received through Gmail (including deleted), everyone I speak to on Facebook messenger, every photo I’ve viewed on Google photos, and so much more. In my astoundment at what I had been presented with, time got away from me and I had spent almost two hours looking through my historical data. It was only at this point, I realised the archive Google had sent was split due to the sheer size. Unbelievably, the collection I had been viewing was one of seven, and there were six more of similar size.

It is an impossible task for me to explain the extent to which my data, your data, and the data of every person you know is being collected and stored. Google is just one example, but these questionable business practices are rife amongst large corporations, and always for the same reason. With an estimated collective market capitalisation of over 5 trillion US dollars, five of the six most valuable companies in the world are large technology companies. That’s because in 2019, data surpassed oil as the most valuable commodity in the world, and these corporations are doing whatever they can to harvest and collect as much as possible from us. Facebook has very much acted as a catalyst in the rise of data harvesting, having over 2.7 billion active users and roughly 52,000 data points on each one of them. That’s an unimaginable amount of data, which can be queried to find trends and draw conclusions in order to target specific individuals.

The Value

Just as companies such as Facebook are hoarding valuable data, hackers also crave it. It is not the case that only freemium model products or services and social media companies are those which are collecting data, and sometimes it is done for good reason. For example, it’s important for your doctor to know personal details about you for medical reasons, and it makes sense for your credit card company to hold information on your financials. But just because you accept that it is necessary for these bodies to store your information, this does not circumvent the value that data holds; therefore it is still a target for those looking for financial gain. Else, why would the NHS have been subject to a ransomware attack in 2017, leading to over £100,000 being paid to the attackers? Or the hack on Equifax in the same year, leading to the data of 143 million people being compromised, and the company spending $1.4 billion on security upgrades since?

A hacker will often choose to retrieve the data of individuals’ then sell it on to the highest bidder on the black market, rather than utilise it themselves. Depending on the data being sold, the buyer may then use it to commit credit card fraud, ransomware attacks, or identity theft. A company’s investment in their cyber security is often not just about maintaining a good reputation and avoiding fines by protecting the data they store; it is also the fact they don’t want anyone else to have it, as this decreases its value.

Because of the endless potential uses of various data sets, it’s not possible to put an exact figure on the value of data, it all depends how it is monetised. But it is clear that if there were a figure on this, it would be more than 0, which is regrettably how it is seen by the vast majority of people today. An account that can hopefully convince otherwise, is that of Cambridge Analytica.

The Motive

Given their headquarters was the building opposite the ProCheckUp London office, Cambridge Analytica is a name very close to home, and one with undeniable notoriety in the data security industry. They demonstrated how data sets as large as those available today can be used to successfully influence and manipulate individuals far beyond just advertising.

Cambridge Analytica created a Facebook application called ‘This is your digital life’, which asks some questions about yourself and determines your personality type based on the answers provided. Hopefully it was a fun and worthwhile experience for the 270,000 people that found out their personality type, because upon using the app, they gave consent for the application to retrieve and store all their answers, all their Facebook data and most importantly, all their Facebook friends’ data. This means even if you had never used or heard of ‘This is your digital life’, it could still know everything about you, even information you had not intended to be public. It only took just under 300,000 Facebook users and a matter of weeks for the application to vacuum up the data of over 87 million users.

Armed with masses of data, Cambridge Analytica found a way to monetise it through joining forces with political campaigns, one of which was the USA presidential election in 2016, of which Cambridge Analytica were an integral part. In short, they took the data of every American of voting age to assess their political standpoint and grouped them into three categories: Democrat, Republican, or Persuadable. Those in the first two categories were ignored, it was the persuadables that were deemed as ‘on the fence’ in terms of political views, and therefore their decision when voting could be influenced. The Trump campaign attacked these persuadables within crucial swing states with targeted advertising, either by shunning the opposition or promoting their own campaign. Rallies were held in regions with a high concentration of persuadables, and protests organised in areas of great opposition. American citizens were unknowingly influenced and manipulated using data they had willingly handed over, and it is no surprise that Donald Trump secured victory in this election given that his campaign ran over 5.9 million targeted ad variations, compared to Hillary Clinton’s 66,000.

The Conclusion

In 2018, the European Union’s (EU) GDPR privacy and security law was introduced, which provides greater data protection and rights to individuals. Though it was drafted and passed by the EU, it imposes obligations onto organisations anywhere, so long as they target or collect data related to people in the EU. This is definitely a step in the right direction for data security, but it’s not enough.

I am not preaching for readers to stop using Facebook, but asking for the consideration as to what information is being collected and whether it is worth it. Facebook knows as much as you allow it to. Meaning that your privacy settings determine how much information you allow Facebook to access. If you want people to wish you a happy birthday and you’re happy having your birthday disclosed, or you want to celebrate the good news of your engagement with your Facebook friends, that’s understandable. But do you really need to fill in a 30-question survey about your likes and dislikes to determine what type of dog you are? Probably not. When you download a new app, what data are they asking to collect on you? Do they really need all of that information, and can you opt out? Are you sure you want to link this app to your Facebook account? You’re willingly handing over your personal data – which we now know has a value above 0 – to another company for nothing.

No, seemingly Facebook is not listening to your conversations through your smartphone microphone, but they do have masses of other data points on you to determine what you should see at any given moment. It knows exactly where you are, who your friends are, what they are interested in and who you are spending time with. It tracks across all your devices, logging call and text metadata and even watches you write something that you end up deleting and never actually send. All of this is being fed into a complex algorithm to essentially predict what you and your friends are talking about, and serve you an advert that is perfectly tailored to your current needs – you are directly affected.

It all started with the dream of a connected world, but now our data is out there and it is being used in ways which we do not understand. Cambridge Analytica was involved in more than 200 elections around the world, and heavily involved with the Leave.EU campaign during Brexit, using the same propaganda and psychological warfare techniques as in the Trump campaign to influence the decisions of British citizens – you are directly affected.

To answer the question at the beginning of this article; who cares?

You should.

Categories